Jorge Luis Borges imagined paradise as a sort of library. People who love books and reading, who still appreciate peacefulness in these high-speed electronic times, will no doubt agree with him.

Cicero, for his part, thought that paradise was a library with a garden. One thing’s for sure: Spain can boast of some truly splendid libraries, like that of El Escorial. Another good example is a relatively modern institution that is a veritable jewel of our heritage. It is a library with a little garden, indeed, and a museum to top it off. In Madrid, at number 20 of Paseo de Recoletos overlooking the Plaza de Colón, stands a building of classical appearance and notable dimensions: the Biblioteca Nacional de España or National Library of Spain, with the Archaeological Museum right behind it. Most Madrilenians and visitors to the city have probably walked by without going up its stairway flanked by statues of Alfonso X the Wise and Saint Isidore of Seville, and even fewer will have dared to enter. For many, libraries may be more intimidating than cathedrals. The National Library, however, is now the site of numerous exhibitions and it’s an easy place to visit. There has been a show, for example, in which visitors could see the world-famous Madrid Codices I and II of Leonardo da Vinci. Even so, that was just a sample, albeit an impressive sample, of the treasures kept in a building that shelters, for instance, one of our country’s best collections of engravings and illustrations, to say nothing of its sections reserved for scholars or its more secret and carefully guarded corners where there are vaults with carefully controlled temperature and humidity containing first editions of Don Quixote, the manuscript of the Poema del Mío Cid, Leonardo da Vinci’s codices, and a long list of magnificent printed works of priceless value. Of course, most of the holdings are now located in robotized warehouses which fill the day-to-day requests of the users and readers at this amazing library.

The library’s director at present is Ana Santos, who is achieving great success in her efforts to make it a more accessible facility. As mentioned, the building itself and the temporary exhibitions which are held here are reason enough to visit this institution, and the library’s gardens are a haven of peace amidst the hustle and bustle of today’s Madrid. Additionally, a wide range of interesting and attractive conferences, courses and diverse activities are always being held. Some time ago I had the opportunity to visit the Trustees Room of the library under the pediment of the building, and it is worth seeing even if for nothing else than its spectacular chandeliers and furniture. The magnificent bookcases there once belonged to Manuel Godoy, who has gone down in popular history as a disaster, the queen’s suitor and the toady of Charles IV. In all truth, however, he was an enlightened and highly cultured nobleman who tried to save Spain’s diminishing power against the pressure of Napoleon, who was seeking to dominate Europe. One of his lovers was Pepita Tudó, of whom there is an excellent portrait by Madrazo at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. In recent years historians have striven to redress the figure of Godoy who, despite his attempts to introduce reforms, met his downfall in the Mutiny of Aranjuez and had to leave the country, where the nobility and the clergy had conspired against him to inflame the people’s wrath. This is an old story now but it is interesting that his personal library with all its books and furniture have been safely preserved in the National Library.

Let us now return to the room where the Royal Board of Trustees of the library assembles. Here we find some portraits that the court painter Miguel Jacinto Meléndez made of Philip V and part of his family for the original seat of the Royal Library created by the king – which gave rise to what is today the National Library. Meléndez was the painter of the royal household until the court moved to Seville for almost four years. There he lost his position to Jean Ranc, who painted what are perhaps the best known portraits of the first monarch of Spain’s French dynasty. Some of those painted by Miguel Jacinto Meléndez, however, are of unquestionable quality, including Philip V in hunting dress, which hangs in the Museo Cerralbo, and this portrait in the library’s Trustees Room. Philip V as the protector of the Royal Public Library is a canvas probably dating from 1727, in which Spain’s first Bourbon king rests his hand on the statues of the Royal Library, the first cultural institution that he founded in our country, on 29 December 1711, wishing “to renew historical erudition and to make known the true roots of the Spanish nation and its monarchy”. He had at his disposal the libraries of the last Habsburg kings and ordered six thousand books to be brought from France. In this way, he sought to enlighten through reading what he clearly considered to be a people of goatherds. Note that we are speaking of 1711, with the War of the Spanish Succession to a large extent settled internationally but not yet over, even though its outcome was clear to see. Indeed, at the end of the war, the monarch saw fit to seize several private libraries of noblemen who had remained loyal to the Habsburg cause.

Getting back to the portrait, we see Philip V with a book, wearing armour and a general’s sash although this painting was intended for a reading room and was to link the crown to knowledge. At his side is his second wife, Elisabeth Farnese, who holds a volume in which may be seen, through a play of reflections and pictorial references, an engraving in which Philip V himself appears, like a book king.

In the same room, hanging beneath the royal couple, one finds the portraits of four of the king’s still small children: Prince Ferdinand, the issue of Philip V’s first marriage and future Ferdinand VI; Philip of Bourbon, the future Duke of Parma and founder of the Palatine Library of Parma, who was also the patron of the celebrated Giambattista Bodoni, creator of one of the most beautiful typefaces ever to have been conceived for printing; María Ana Victoria of Bourbon, who was engaged –from the age of three– to Louis XV but was finally to marry Joseph I of Portugal; and lastly, Charles of Bourbon, the future Charles III, in a portrait in which his famous Bourbon nose is not evident. Perhaps Meléndez sought to beautify the boy or maybe his nasal protuberance was not yet notable.

Although he was an exceptionally long-lived king, it may be thought that Philip V never came to hold the Spanish in any great esteem. Indeed, it would appear that he never understood them and never came to like them. What’s more, he was prone to melancholy and depression, if not to say to episodes of mental derangement. His abdication in favour of his son, who reigned briefly –for less than one year– as Louis I, is another fascinating aspect of history that rivals a good novel. Now he is a king who is reviled if not outright despised in Catalonia and in a large part of the Valencian country (his portrait continues to hang upside-down in Játiva), but in today’s troubled times it would be worthwhile to visit libraries more often and to read there in order to better understand our past. Indeed, at the National Library there is a whole forest of books just waiting to be explored and enjoyed.

A few more notes

A precedent of the legal deposit was established in 1716 and the Royal Library, which subsequently became the National Library of Spain, began to keep a copy of almost everything that was printed in the kingdom. What’s more, the monarch issued a privilege so the Library would have a right of pre-emption on any books to be sold in Spain. This led to a dramatic growth of the library, which even came to possess its own print shop and type foundry at the end of the 18th century. The 19th century, with its wars and disasters, started off badly for the library, but it soon acquired today’s building, on the site where an Augustinian Recollect convent had stood. In 1866, during the reign of Isabella II, the construction of the present-day building began, and the library was inaugurated in 1892, opening to the public in 1896. There is also a handsome statue of Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, the Spanish scholar who directed the National Library in the early 20th century.

A forest of books

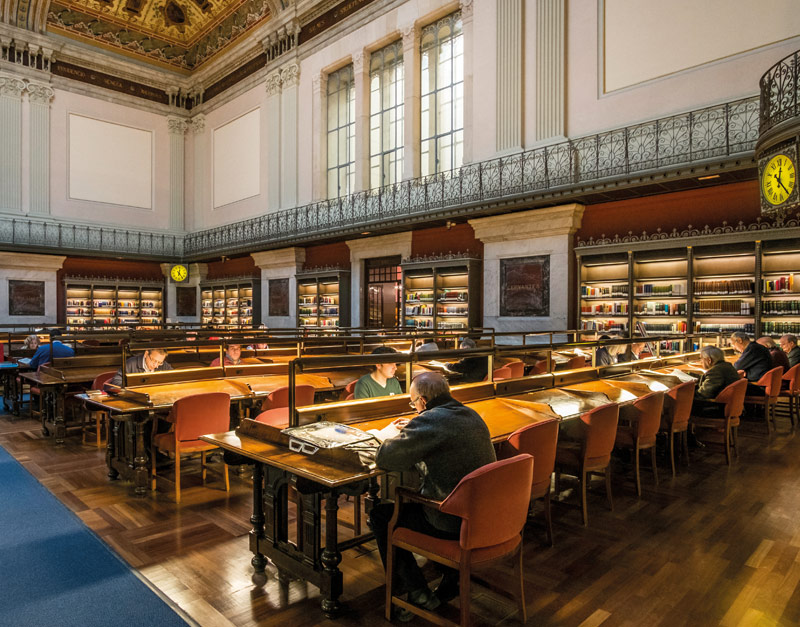

The National Library contains over 30,000,000 publications of all types: sheet music, books, magazines, maps, engravings, illustrations and brochures. The map collection alone would suffice for a lifetime of contemplation and study. For public use, the General Reading Room is reached after passing a security control and attending to some minor administrative formalities. The fact is that most of the holdings, and above all the more recent publications, are kept in some enormous warehouses in Alcalá de Henares, but the old building on Paseo del Prado is a jewel in itself, with its double stairway and its reading and consultation rooms. As mentioned, the building is shared with the National Archaeological Museum, which has recently been restored and features a new layout. For a cultured visitor, spending a morning between the two institutions can be an exciting experience that will long be remembered.